First of all, how about that title, eh? The movie could be a heap of shit and it would still win points for the title, which sounds like some lost French new wave picture. Éclat de Silence, avec Alain Delon. But no, it’s an American film noir, albeit a pretty curious one. It’s from 1961, making it one of the first crime dramas to come out after the widely-accepted-by-me death of noir at the hands of Alfred Hitchock’s Psycho. It’s also odd insofar as it’s less the kind of B-studio crime drama that we normally associate with the noir genre, and more of what would become a small-studio independent film, from the mind of a genuine if marginal auteur. The now-retired Allen Baron had a fruitful career in television, reliably directing a number of network favorites, but he started out at age 34 writing, directing, and starring in this passion project. It was well-enough received at the time of its release that some critics (with, admittedly, an oversalting of hyperbole) called him a new Orson Welles, but Hollywood too felt the time of the noir was over, and Blast of Silence got minimal studio support. Too late to be a real Hollywood noir director, too early to jump on the ’70s maverick bandwagon, Baron was an unlucky director who happened to be just out of his time, but he left behind a single undeniable item of evidence in support of his genius.

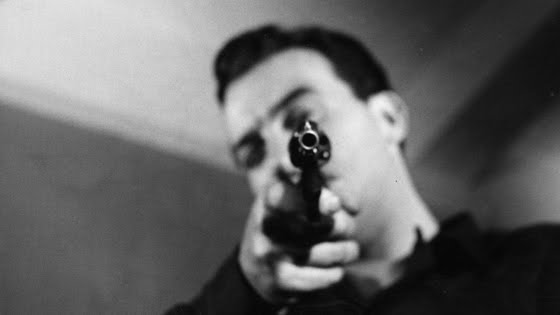

Baron plays the role (originally written for his friend Peter Falk) of freelance killer Frankie Bono, a self-loathing and passionless killer whose only talent is for murder. He’s a blank-faced cipher with a suitcase full of brand new shirts, in New York for Christmas to take advantage of the season’s lessened police pressure to knock off a mid-level mobster. Frankie hates his clients — they just get in his way — and they hate him, seeing him as the murderous presence that may one day come after them. He engages in petty cruelties, stepping on his client’s foot just to remind himself he’s in charge. Lucky for him, he hates his victims too: the latest, Troiano, is an overreaching hood with “lips like a woman”. He even hates the man he visits to buy a clean gun for the job, Ralph (a terrific little performance by Larry Tucker), an obese bohemian sad sack with stained shirts and pet rats. He hates Christmas, he hates parties, he even hates an old friend he runs into at dinner; hate is what keeps Frankie going.

The one person he doesn’t seem to hate — and who doesn’t hate him — is Lori, his old friend’s sister. She remembers him from the old days, quite an accomplishment for a deliberate nonentity like Frankie, and she feels a difficult combination of attraction and pity towards him. She gets him to tell a story of his post-orphanage days (true or a lie? It doesn’t much matter; it’s astonishing enough she gets him to string more than three words together), and he goes to her house for a date that turns into a touching display of need, and then into an ugly display of desire. Molly McCarthy, who plays Lori as a simple, self-respecting, decent, and caring, woman, but plain and not used to asserting herself, has a hard job of it: she has to try and bring Frankie out of himself after he comes close to raping her. She’s smart enough to know that he’s profoundly damaged and needs something to make him human, and perceptive enough to see that he’s not used to self-expression, or to being around people in anything but the most brutish of ways; but she’s not well-acquainted enough with the dark side of humanity to realize how poisoned he really is. She can’t save him, and from that point on, the filming gets more sophisticated — there are some tracking shots and set-ups that are fantastic — as the violence gets more intense and savage. It ends with the literal force of a hurricane.

From its first words — provided on the sly by Waldo Salt — to its last frame, Blast of Silence is an existential noir, which only reinforces its essentially European nature. While the whole thing reeks of Scorsese’s alienation, Jarmusch’s urban desolation, and Tarantino’s sleazeball philosophizing, American audiences apparently weren’t quite yet ready for a movie that begins “Remembering out of the black silence, you were born in pain.” The idea of a hired killer undergoing an externally-triggered crisis over the essential nature of his work wasn’t exactly new, nor was the film’s extraordinarily misanthropic viewpoint of a man who found something to hate in everyone, especially himself. But something about Blast of Silence, or some combination of things — its complex psychology woven into a simple narrative, its Sartrean sense of human revulsion, its lead character who says maybe a dozen words in the movie’s first hour — made it step hopelessly out of synch with the public tastes at the time, which were moving towards the pure and polished. Criterion got it right, though; few films deserve a second chance at finding their audience more than this one.

Man, that third graph is a thing of beauty.