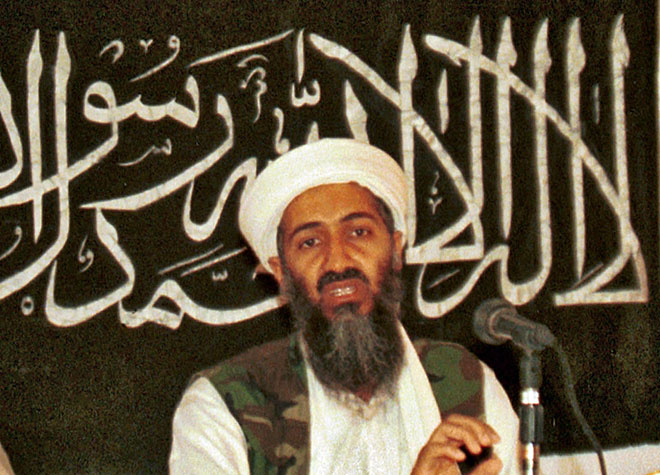

Osama bin-Laden is dead.

Everyone is supposed to have an opinion about every aspect of how that sentence came to awarded the status of truth, and I guess I do, but I’ll be damned if I can sort it out into anything worth saying. Mostly, I feel a combination of relief that a man who was only doing harm in this world is no longer able to do so, and a frustrating — and familiar — sensation that no opinion I could hold on the matter will possibly make the slightest bit of difference.

As an atheist — more to the point, as a person who does not believe there is a world after death in which punishment or reward will be meted out — temporal justice is very important to me. It maddens me when violent men who have climbed to great heights on the suffering and death of others die abed, having been little more than inconvenienced for their crimes. I am not an advocate of nonviolence, because violence rarely answers to any other master. And there are more than a few people I would be happy to see suffer for what they have done. But, as a wise man once said, you can’t cut the throat of every cocksucker whose character it would improve. I’m only slightly more troubled by the existence of an Osama bin-Laden than I am a government that gets to decide which people get to walk the Earth and which ones don’t. And the Wicked Witch may be dead, but his flying monkeys are just as pesky as ever, and we can’t afford to maintain the Yellow Brick Road anymore.

Hacky metaphors aside, I keep trying to put myself in the position of those who cheered the news. It’s easy for me to find that reaction a bit skin-crawling, since I didn’t lose anyone dear in the 9/11 attacks; but then, there’s hardly a Palestinian alive who hasn’t had a friend or relative imprisoned or murdered, and we’ve all pretty much agreed that their habit of whooping it up after a terrorist bombing is a little creepy. That the reaction came especially from young people with minimal investment in the original attacks on America gives the whole phenomenon an even more flustering dimension. I think back to World War II, as everyone does when prepping their current events analogies: Jews in camps cheered when they were liberated. Americans back home cheered when the war was over, because the boys were coming home. Did any victims of the concentration camps dance giddily at the news of Hitler’s death? Did our parents and grandparents stateside throw a party when it was announced Nagasaki had been evaporated? Possibly, even probably. And it’s not my place to condemn anyone’s emotional reactions, then or now. But we don’t choose to remember those cheers, if only because we still maintain a vestigial sense of shame. I can’t help thinking that if you’re cheering the death of another human being, rather than what that death means (which, in this case, might very well be nothing), you’re accessing an ugly part of the brain.

In practical terms, too, the Arab problem (that is to say, the innumerable foreign policy frustrations we have conveniently defined as ‘the Arab problem’) is one that’s been approached with force, and only with force, for close to a century by us, by the British, by the French, by Israel, and by just about anyone else who cared to stick a toe in. That it may have responded to force in this instance hardly changes the fact that we have been officially out of ideas for dealing with the Middle East since at least the 1960s. This space has previously featured a discussion of the lamentably bad results we’ve gotten out of our explosive ordnance diplomacy in the past, and hardly needs to be rehashed here; and while I would never question the courage of the men who took down bin-Laden — an act of bravery beyond anything I have ever or will ever face — I have to concur with Noam Chomsky, who observed that the world is absolutely flush with heroes, and could use less of them and more people with good ideas.

Good ideas are sorely lacking in our approach to the ongoing crisis (political, criminal, military, economic, diplomatic) in the Middle East, which is why I view the demise of bin-Laden as of less than world-shaking importance. There’s no indication as yet that it will alter in the slightest the progress of our directionless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, both of which were ostensibly begun as a response to bin-Laden’s handiwork; and we have recently opened up a third front in Libya, which features the same old ‘drop some bombs and hope for the best’ approach we’ve been using since Ronald Reagan sent gunboats to Lebanon. The chances of an Muslim equivalent of Gandhi emerging from the region decrease with every bomb we drop, with every Arab shot at a checkpoint, with every iteration of the trope that these are a people that respond only to force.

And it is Gandhis that are needed; it is Martin Luther Kings and Aung San Suu Kyis. Theirs is the perspective that is lacking, and theirs is the voice that should be heard. It occurred to me, as I was sitting here last week trying to make sense of all the conflicting information coming from the news reports of bin-Laden’s death, that violence is so inculcated in our minds that it even corrupts our dreams and innermost desires. The punishing conservative dreams of warfare against the unrighteous, of punishment and pain for the disloyal; the caring conservative dreams of revolution against the corrupt, of justice against the unjust. I am as guilty of this as anyone. Who dreams of reconciliation? Who, in their secret thoughts, imagines themselves as a bringer of peace, a creator of new social solutions, a dedicated bureaucrat working for change? Whose hidden self is not a warrior, a killer, a vigilante or a righteous avenger, but an advocate, a healer? Who composes speeches meant to bring about lasting societal change, not spur the masses to fight? There is no glory in it, there is no heroic moment, only recognition, inspiration, dedication, and hard work. We will never see the heads of state seated tensely around a monitor watching a poor family struggle to make ends meet, or a man caught in the contradiction between the freedom he wants and the freedom his society allows; only gunfire and bodycounts will ever come through that monitor. It was JFK who said that war will persist until the conscientious objector is held in the same esteem as the warrior. Judging from recent events, it is not only that we have reaffirmed that being a humanitarian is not as worthy goal as being an assassin; it is that we no longer believe an end to war is a state worth pursuing. The nightmare may be dead, but the dream may have died with him.

Couldn’t agree more, LP. I suppose the process of “thinking outside the box” re: social issues is something that typically takes a LONG time to really settle among the masses. And in my view, there were some strong breakthroughs in unconventional peace-based thinking in the ’60s and ’70s, but we’re still working on how to maximize their utility. An optimist might say that the warmongering “Devil” here — of which someone like, say, Donald Rumsfeld is a representative archetype — is, in the long run, doomed to burn Himself out (while doing some significant damage along the way, of course.)