Ida Lupino’s The Hitch-Hiker breaks a lot of the ‘rules’ of film noir, and in doing so, it sometimes scans like a prescient warning bell of the post-Psycho revolution in crime drama than it does a product of the 1950 B-picture system. This is by no means meant as a criticism; a few clunky plot points and a pocket-change budget aside, it’s a terrific little noir that deserves a wider viewership than it’s gotten due to having fallen into the public domain. But its creepy psychological angles, horrific true-crime backstory and unusual choices within the standard genre framework make it an outlier, to be sure.

The plot — by Lupino and her husband Collier Young, based on an original story by noir stalwart Daniel Mainwaring — is simple enough to barely justify its hour-long run time: two rock-solid middle American guys out on a fishing trip lucklessly stumble across a spree killer, who orders them to drive him to Mexico while cruelly breaking their psychic defenses. It’s a story with no twists or gimmicks, as straight-ahead as a remote desert highway, but like most of the best noir, the devil is in the details. Lupino was competent if unexciting as a director, but as a writer, and more importantly as a crafter of mood, she was quite gifted. Robbing noir of its social qualities — of the quirky characters and eye-pleasing settings of the urban jungle — was a tough trick to pull off, but she manages to convey the necessary tone of doom, paranoia and slow-boiling disaster by isolating her characters in a car, where simple proximity creates dread and hostility.

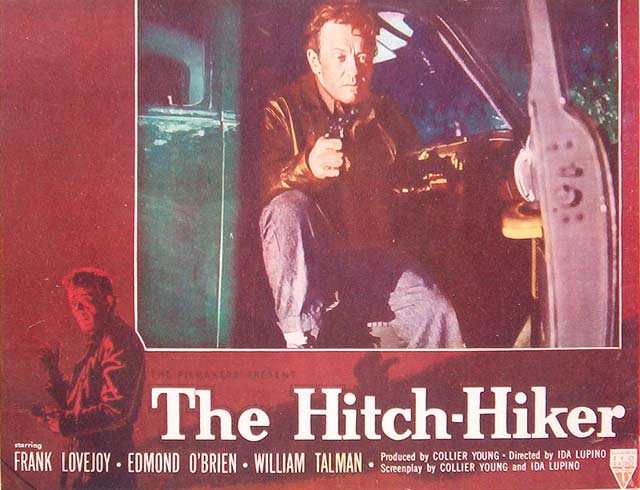

Those characters, too, are outside the lines of most noir; Frank Lovejoy turns off his steely cop routine and Edmond O’Brien recontextualizes his knack for playing panicky lugs when they team up to portray a couple of absolutely colorless everymen who get stuck in the ultimate road-trip nightmare. William Talman, a universe away from luckless schmo Hamilton Burger, is fantastic, with his drooping eye, loping frame, and terrifying sleeplessness, but he’s not a noir villain; he’s a pure psychopath who wouldn’t be out of place in a ’70s thriller. His random murder of innocents (which actually had to be toned down for the film) removes him from the world of profit-driven crime, and while his determination to break Lovejoy and O’Brien, to reduce them from optimism and hope to terrified compliance and, ultimately, to numbed despair, has precedents in, for example, Key Largo‘s Johnny Rocco, Rocco does it to exert power; Talman’s Emmett Myers does it purely for sport. He is a thing of malevolence, not greed, and his victims are so out of their element, lacking any guile or familiarity with the underworld into which they’ve been cast, that The Hitch-Hiker plays much more like a modern psychological horror film than the grim noir it really is.

Lupino had very little money or resources to work with, so she made as much as she could out of a bad deal from the studio; she makes the best of her limited ability to shoot on location, and brings a sense of loneliness and remoteness to the desert and highway scenes that’s a reversal of the oppressive enclosure of the standard urban landscape of noir. The petty hoods and schemers of urban noir experience terror at the idea that someone is watching, while the innocent Lovejoy and O’Brien are traumatized by the certainty that no one is watching. She did her research, too; Talman’s character is all the more vivid because he was based on a real-life spree killer named Billy Cook, who wiped out an entire family a few years before The Hitch-Hiker was filmed. She gave Talman extensive notes on Cook’s psychology and behavior, right down to the slack eye and the loose carriage, and she peppered the script with quotes gathered from personal interviews she conducted with the real men upon which Lovejoy and O’Brien’s characters were based. Finally, she had the good luck to work with the underappreciated cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca. He lends some serious chops to the camerawork, and while it’s not always apparent, there’s enough there to believe that a decent restoration of the movie would reveal some hidden wonders.

Noir is often referred to as a male medium, though that’s more of a testament to the sexism of the studio system than anything else. Much is made of the fact that The Hitch-Hiker is the only American film noir by a female director, and Lupino said she likely wouldn’t have had the chance to direct if she hadn’t already made her bones as an actress. This isn’t an effective condemnation of noir itself, though; it’s not as if every other genre in Hollywood prior to 1960 was teeming with female directors. The pedigree of noir has more women than most, at least in the source material; outside of weepers and ‘women’s issues’, crime drama and detective fiction was one of the few places that offered decent opportunities for female authors. Sexism was — and is — a Hollywood problem, not a film noir problem.

The thornier debate is whether or not noir is an inherently sexist genre, particularly in the context of one of its most prominent features, the femme fatale. There’s good arguments to be made on both sides, I think. Women certainly weren’t given much of a fair shake behind the scenes, it is true, and on screen, they usually fell into one of three categories — the loyal girlfriend/lover, the helpless victim, and the scheming femme fatale. The cold-hearted, greedy killer, betraying her man for a shot at the big money, isn’t the most progressive image of women on screen, either, and while an occasional female role was written that called for independence, intelligence and inner life, they were still usually seen in relationship to a man. On the other hand, again, this was (and is) a problem endemic to all Hollywood product, and in the role of the femme fatale, we at least saw women with agency. They may have had murder in their hearts and poison in their kisses, but at least they were determined to do something to avoid eating the shit that life handed them, and even if violence and deceit were the only tools given to them, they at least put them on equal footing with the men. If the women of film noir could not earn respect, they could at least teach fear.

Still, though, the example of Lupino aside, the boy’s club mentality didn’t allow for much expression by women. (Ironically, for the only film noir directed by a woman, women are basically invisible in the world of The Hitch-Hiker.) The fact that she left behind this one highly compelling relic, a crime drama more cheaply produced and clapped together than most, but one more deeply felt and starkly observed as well, leaves us to wonder what else we lost because of Hollywood’s golden age of sexism.