It was famously said by a man who had never been there that Hell is other people. Like most epigrams, it’s more clever than it is accurate. Hell is other people, yes; but not many. The energy and logistics involved in getting a dead man’s shade into Hell are so vast and complicated that it’s a fate generally reserved for those select few who have made a great deal of trouble for one of the celestial beings still capable of sending them there. If sinners were coming through the gates of Dis at the rates indicated by these gloomy-minded physicians of the soul, the construction costs alone to house those blameful billions would have bankrupted even pecunious Plutus himself a thousand years ago.

There is also the matter of demons; they nearly outnumber the damned, and most of them have far more important things to do than waste their days and nights (although it is mostly night, down below, so far away from the sun) jabbing and searing some hapless ghost for what he did twenty centuries ago. Not that the demons don’t do what they are told; they fulfill their ancient duties, with a fiendish creativity that would cause a substantial moral renaissance were its application more widely seen. But it’s a very small part of their overall duties; they have no more spent all of the last five thousand years torturing mangled spirits than mankind has spent each waking moment since the capping of the Pyramid of Cheops inventing new vegetable dyes. And this is not to mention that more than half of Hell is off limits to the damned; the rest of it is a storehouse for the titanic wealth of Plutus and is manned only by a few minor devils who act as his functionaries, financiers and factotums. If one is seeking damnation among his peers, he’d be better off staying on Earth.

None of which is to say that it’s not as unpleasant as they say. Even Pluto’s realm is a charnel counting-house; it resembles some chthonic bat-haunted cave, rank with staleness and sulfur and greed, and for all the gold therein it is devoid of luster or ornamentation. Not for nothing has its builder forsaken the underworld for above-ground offices and banks, his pleasant earthly houses of worship, designed with clear intent to resemble the ancient temples of his gilded age. And the maddened, screaming, inward-turning chambers of horror belonging to his junior partner, the light-bringer Satan, are easily as bad as they are portrayed in the tales told by those who caught a glimpse of them in some remarkable nightmare. There is no sulfurous pit, no lake of fire; only endless, barren, cramping rooms and twisted shrunken halls of lunatic design in which all but the most clever old demons become forever lost. Satan’s half of Hell is where centuries of torture are interrupted only by the unspeakably cruel hope of escape – a hope that is immediately supplanted by despair when one finds nothing lying outside the bounds of one’s personal oubliette but blighted, lonely wandering, until one returns, hopeless, and begs for the comfortable familiarity of torture.

Hell is supported by ancient contracts: covenants, treaties, terms of surrender and a thousand other diplomatic agreements accumulated over stockpiled centuries where the immortal and unspeakable had little to do with their time than play out such little transactional games. As its founder and majority shareholder, Plutus holds sway, and Hell is still given over largely to matters of profit and possession; Lucifer, having acceded to some rather onerous conditions as a result of his embarrassing trouncing by the armies of Heaven all those ages ago, does what he can to supervise the pointless torment of the privileged dead. Each finds the other an agreeable, like-minded partner, and both are amenable to the other’s occasional plots and diversions (Plutus being particularly fond of any new profitable enterprise, and Lucifer ever interested in temptation, corruption and the bringing low of what was once high). However, it must never be forgotten that each is his own man, and the loyalty that binds them is that of treaty-tied warlords: they may dine together and laugh together and plan mad adventures together, but any advantage must be seen as the sole property of one. Theirs is the camaraderie of sociable executives or rival pirate captains, lifting their glasses together and smiling, but each with his hand on a hidden dagger. If you asked Plutus what he thought of Satan, he would paint you the picture of a creature embodying all the best and most noble qualities of life unending, and Satan would return the compliment most sincerely; however, if you asked one if he trusted the other, he would favor you with a look similar to the one you would receive if you asked two fish if they ever went golfing together.

Most of what has been written about Lucifer comes from sources that are either overly hostile to the mere fact of his existence or by people who admire him in the way that only someone who has never met him can manage. Since these sources cannot even remotely be given authority on the subject of the light-bringer, clearing up the many misconceptions about him is a fiendishly difficult task, akin to writing an accurate biography of fire. Many people assume that since Satan was such a favored presence in Heaven back in his angel days, he must have a personality nearly identical to that of his former employer. In fact, he is nothing like the monstrous authoritarian Jehovah; his rebellion was not that of the ambitious usurper or of the moralistic freedom-fighter, but of the chronically frustrated middle-manager who is tired of never being able to get anything done because of the short-sightedness of the owner. He spends almost none of his time in Hell bullying about the demons; he runs a tight, largely self-governing ship with endless micro-tiers of authority and responsibility, with presidents and dukes and lords of hours by the score all reporting to one another in a labyrinthine hierarchy that its inventor is pleased to point out eventually became the norm on Earth. Instead, when he is not elsewhere, he usually retires to his throne room and pursues reading, writing, and arduous study; the rest of the time he travels to the world of men to apply what he has learned. His enormous reputation among the celestials rests on this: he has made better use of his unending time than anyone. It is scarily accurate to say the devil is in the details: so he is, in every single one, and what’s more, the details are in the devil.

This fact lies at the heart of one of the key deceptions as regards his “fall from grace”, as it happens. Jehovah’s people, recognizing from the start (for His reign was still young then, and He still faced detractors from all corners of the life beyond life) that they needed a plausible explanation of why the individual in whom they were busily investing all the qualities that are horrid and sinful and vile in the universe had at one point been the City of God’s golden boy, hit upon the bewildering claim that he was “the fairest of all the angels”, and that God favored him because he was so beautiful. It was a bad idea from the start, and a stupid bad idea at that; Jehovah’s advisors were generally chosen for their skill at arms rather than their ability to craft plausible propaganda. But like a lot of other bad ideas, it got firmly entrenched very quickly and soon it was too late to back away from it without looking foolish, and God cannot afford to be made to look foolish. So they simply held onto it, worked with the shabby materials they had at hand, and wouldn’t let it go until no one really cared anymore. Certainly Satan was handsome, as angels go—even now, after eons of living in the worse place imaginable, he was tall and proud and dark, with a cruel smile and hair black and sharp like a raven’s beak — but his real gift was that he was tremendously intelligent. And, seeing as smart people have always been valuable to power, he became Jehovah’s right-hand man almost from the beginning.

However, being intelligent almost always backfires in this regard: anyone bright enough to make major beneficial changes in an organization will sooner than later be bright enough to ask himself why he’s not the one in charge — which is exactly what happened with your man the Devil. Alas for him, though, the time at which being smart was more important than being strong had not yet dawned (and, for that matter, still hasn’t), and his little band of clever, dedicated, high-minded rebels were handed their asses in less time than it takes to say the Lord’s Prayer by Michael and his vast army of not particularly bright but extremely well-armed and ruthless angels. His intelligence didn’t completely let Satan down, of course – God’s lack of foresight kept Him from realizing that the best thing to do with Lucifer and the rebel angels would be to cut off their heads and stick them on the golden spires over the gates of the Holy City, rather than just exiling the insurgents so they would live to cause trouble for Him for the next six thousand years. Satan, having no such fault, made a list of the brightest, most ambitious people in what remained of his army, and had them all quietly executed – all save one. That one he sent to Heaven to negotiate terms of peace, while the light-bringer himself bargained with Plutus, trading his assistance with a number of the god of the netherworld’s long-term financial projects for a healthy chunk of subterranean real estate. He then set to work implementing a number of ideas that would pay tremendous dividends over the next few thousand years both personally and professionally, including bureaucracy, democracy and the notion of private property. He set up a massive hierarchal chain of command, which would assure through total interdependence and a cut-throat promotional scheme that there could never be a serious challenge to his rule. Finally, having done all this and set into motion a remarkable expansion plan for Hell which continues to this day, he spent much of the next few millennia on Earth, wondering what to do next.

Satan did not normally spend much time around the damned; he was usually in the mortal world, in one of his three favorite guises (the Man Who Tells You Exactly What You Want To Hear, the Man Who Says Things That Seem Too Good To Be True, and the Man Who Asks ‘Why Not?’) , undermining this and destabilizing that. He found the shades depressing, single-minded and generally incapable of taking the initiative in anything; even on those rare occasions that he did let them escape, they ended up either begging to be let back in or heading right back to Earth to pick up on the exact same things that got them sent down to begin with. Still, he liked to keep a hand in; every so often one of the damned led a life so degenerate or dissipated that much could be learned from it, and if nothing else, talking to the hell-bound gave him a good handle on whatever was driving Jehovah to distraction at the time. Lately it seemed to have been sodomists, musicians, and a group of long-winded Frenchmen – a rather limited menu for Satan’s particular intellectual appetite — but he had hopes that someone worth a word or two between roastings would turn up in his latest tour.

There had been a few times when he had even violated the covenants and released someone from eternal damnation because he thought them to be potentially useful enough. Jezebel, for example had been one of these; her drive, capable administration, and utter lack of respect for God were such that since he had freed her, she had become one of his most valued assistants. He desperately wanted to release Jesus, the King of the Jews, from his maddening torment; the deluded rabbi had been invaluable to Jehovah, allowing Him to pull off an epochal public relations coup with almost no effort on his part. The Galilean mortal, acting entirely on his own, had preached a great deal of contrascriptural nonsense about love and forgiveness, all the while half-claiming to be the son of God (ridiculous, of course – a notion borne on lunacy’s wings) , which is why Jehovah had him killed in the first place.

What the Lord hadn’t realized is how popular the rabbi’s teachings would prove to be; once He did – and realized this was a chance to advance his cultural dominance without actually changing his ways, a chance to reinvent his popular image to a new generation of evangelists without actually becoming what he had no intention of becoming – he located a handful of dedicated partisans to get the word out, hired a fanatical Tarsan to mix some theological rectitude to the poor Galilean’s muddled teachings, and sat back and reaped the rewards of the amazing serendipity. If word were to get out that Jesus was not Jehovah’s son – and worse, that Jehovah knew it all along and cynically reaped the rewards of his teachings while allowing him to bleed and then burn – it would be very bad for Him, and that would be very good for Satan. Alas, the Lord of Heaven kept the rabbi under the closest watch, and had made it crystal-clear that any interference in his punishment or imprisonment by the Prince of Hell would be received as an act of war. S

atan had no such high hopes for the current crop of shades, but even in his dark kingdom, hope sprang eternal. On this particular night, Lucifer (just returned from a meeting in Texas, mandated by Plutus, with some real estate developers and petroleum executives who were more than willing to nod their heads in delighted agreement with everything he’d had to say) was feeling restless. He had been on Earth for several years now; a whole new cycle of shades had arrived in his absence, including some who he’d met, still living, when his most recent trip began. He was not particularly looking forward to the obligation of visiting the new arrivals; he’d brought back a large amount of computer equipment and was anxious to install it – it had served him ridiculously well up above. He’d also acquired a number of books on the subject, and had a few bright young stars in the hi-tech firmament on his payroll with the usual contract. But he had a reputation to uphold and a duty to fulfill. It was time to make his rounds.

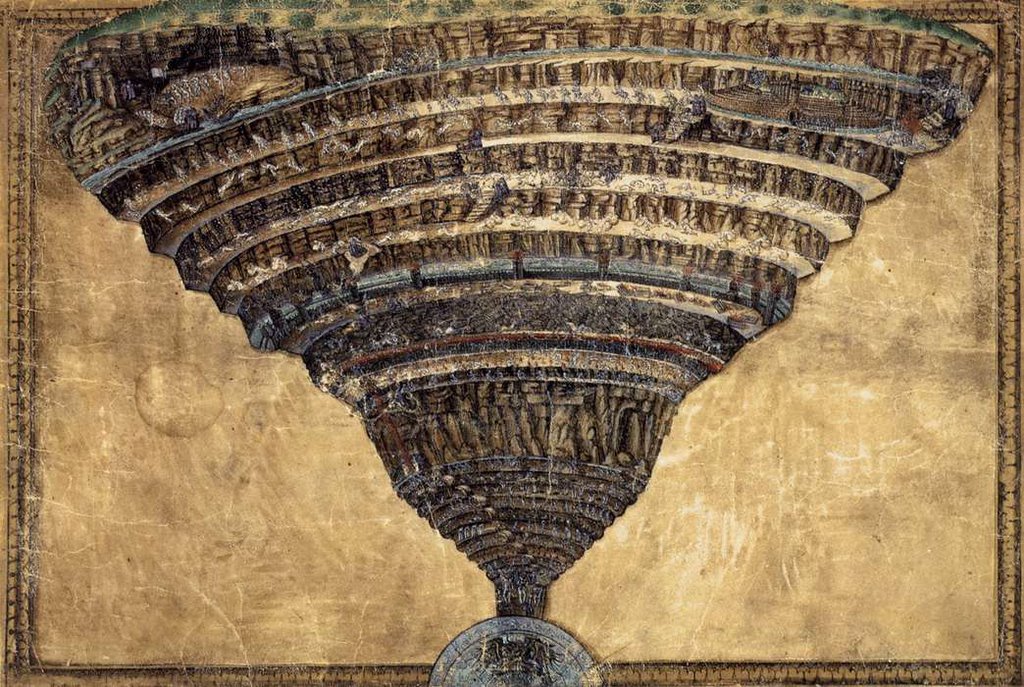

Pausing briefly to make the usual small talk with Beelzebub, Mephistopheles and some of the other higher-ups on his staff (there would be plenty of time for official business at one of the Monday morning meetings of which the Prince of Hell was so fond), he left his throne room and walked, lost inside himself, out of the Great Hall and out into the downward circles. Taking this route, moving from the embarrassingly grandiose (and, quite frankly, derivative of the house style in Heaven) faux-majesty of his offices and high seat to the provocative, crushing horror of the Nine Circles, each one smaller, more intricate, more brilliantly designed, and more terrible and insular than the one before, always put him in mind of the demon who had built it.

Mulcimer was a rarity among the undying in that he had stopped aging when he was an old man. As a result, he seemed perpetually ancient, and no matter how many decades he burned away, he always looked like he was on the verge of death. This, in addition to his profound talent and the warm relationship he enjoyed with Lucifer, caused the other demons to treat him with a great deal of respect, even tenderness, which he returned with annoyance and irascibility. He was difficult to speak with and impossible to know, but everywhere Satan walked, he saw where the Architect of Hell had been. The Prince of Hell had always admired Mulcimer, since it seemed that he alone (besides Lucifer himself) had possessed the will and drive to perpetually develop, change and reinvent himself through the endless night of immortality. When Satan and the rebel angels first arrived in Hell, it was nothing but a huge, desolate cluster of colossal underground caverns and a small compound (placed there by the ever-accommodating Jehovah) that resembled a prison camp. It was the still-infant talents of the old man (who was then actually quite young, relatively speaking) that designed the regal, ostentatious throne room that Satan had called home these many millennia, but his real brilliance was still to come. It spoke in a voice one could see when one left the royal rooms and wandered to the places of tortured souls.

In a quite literal sense, the old man had been an evil genius. He was an artistic locust, building up an fierce chitin of style and skill, then leaving a perfect replica of the man he was at that time, formed of stone and steel and marble and wood and insanity and pain, before shedding it to become something new, something different, and flying off to devour some new project, style or idea. The Second Circle betrayed a young and ambitious soul, a man too literal and with limited erudition, but who nonetheless had begun to embrace a dark critique of architecture; he was perhaps not pleased with the dread prison where fate and his own choices had led him, but he had fully accepted that fate, and was as determined to excel in the construction of a palace of horrors for the dead and doomed as he would have been if he still toiled for the greater glory of God. In these first designs – for Satan, realizing both Mulcimer’s passion and genius and his own inevitable need to expand his realm, had designated him the Architect of Hell from their very first hours in that pit of defeat and ruin – the old man showed a certain naivety, a showy confidence that paid more dues to arrogance than innovation or skill.

But by the time construction began on the Third Circle, with its bewildering microclimates and disorienting open areas which seemed too large for the space allotted them, he was a changed being. He had spent several hundred years studying his craft, learning his trade, selflessly seeking out any demon or shade that could share a new perspective, a useful bit of information, a set of eyes not his own. The Fifth Circle, that watery darkness, that empty awful inversion of the vastness and life of earthly seas, was the old man’s first triumph, but certainly not his last. In despair and insanity and torment he found his métier, and working in an ever-decreasing scale but with ever-increasing complexity, Mulcimer’s work became greater and greater with subsequent additions. With the addition of the Sixth Circle and the insane crypto-metropolis of Dis, a Taj Mahal of torture and madness, Satan recognized a true kindred spirit. The Prince of Hell approached him and offered him a presidency. Once Mulcimer completed the brilliant black tangled forest of the Wood of Suicides, his patron asked him if he would like to incorporate on the Earth, to visit the world of living men and see the works of mortal masters, to learn from sights and not books, to ask questions of men who were not yet wracked by perdition. The architect had leaped at the opportunity, and while there, developed his only vice and the solitary passion that gripped him with as much intensity as did his craft: he became extremely fond of wine.

Even here, he approached it as a creator and a possessor, not a mere drunkard; many times he enlisted the staff in attempts to create Hell’s own vineyard, to rival the extraordinary vintages that sprang from the Fields of the Nephilim in the City of God, but it was one of the many torments of Hell that nothing would grow there. Still, the Prince of Hell felt for the old man, and would send imps to fetch him rare and exquisite tipples from the world above. It was a tremendous expense for no practical gain, but Satan felt the old man’s talent and ability to not waste the gift of unending life should not go unrewarded. Eventually, however, no matter how intricate his designs became, no matter how perfectly and gracefully they reflected the infamies that were carried out within their concrete realizations, the old man became tired. He wearied of life unending and on their frequent walks through the tiny, labyrinthine passages that had grown into reality from their birth in his amazing mind, Mulcimer, bibulous and frail, would complain that he was losing his desire. “The day is coming,” he would say to his benefactor and friend. “The day is coming.”

f“What day is that?” Lucifer would say, “Christmas?”

He enjoyed needling the old man. He knew that as long as Mulcimer lived, the spark of a brilliance that predated Hell would not forsake him. But eventually, he forsook the spark: not long after the Ninth Circle was completed, the Architect of Hell abandoned his immortality. So frequently had the rougher demons joked about how close the old man was to death that they were shocked to silence when it finally happened; but it was true enough. He let himself stop living, in his tiny beautiful apartment in the rear of the Halls of Judgment in the Second Circle, among his designs and his books and his tools and his beloved wines. The crass young devils, the crude and ambitious latecomers who were governed by fear instead of respect, hissed that the old man had lost his gift; but Satan knew better. Mulcimer had simply become bored. He took no more joy in his work (although it didn’t show); he believed that life had no more to show him, and so he gave it up.

Satan had ambition, responsibility and commanding desire to drive him; but, like so many of the immortals cast down to Earth after the great war, Mulcimer finally had nothing left to not die for, and so he died. The date of his death was declared a holiday in Hell, and the Devil allowed the shades to wander freely, to see what mighty work the old man had done; and since this never failed to sharpen their despair, Heaven looked smilingly on the deviation. Memories of the old man nagged at Lucifer as he walked (he enjoyed walking through his kingdom; he never flew and rarely allowed himself to be driven, except when time was of the essence, which it tended not to be, since everyone he ever dealt with was immortal).

The tedious mucking around with yet another in an endless series of self-absorbed, short-sighted, greed-consumed mortals from which he had just returned had left him listless, frustrated and filled with unrest. It had been too long since he had done anything exceptional, since he had seriously advanced his cause, since he had broken out of his routine of duty and contemplation; if he was to ever gain his revenge on the Lord of Hosts, if he was to avoid the death of ennui and blunted purpose that took his old friend, it was time for him to put his studies into action. It was time to remind God that he had a nemesis in more than name. He bore his concern like a cloud of gnats on his high furrowed brow, and the demons, sensing in him a great turmoil, dared not speak as their Prince moved through their presence.

There were more demons moving about Hell than was usual, especially given the slowing in the arrival of new souls: initial plans were being drafted for an Eleventh Circle (the Tenth, partially designed by Mulcimer prior to his death, had been subcontracted out to a group of talented mortals, who, judging from their reaction when they received the specifications, were not quite prepared for the reality of it; work nonetheless continued, and the lamentations of the builders and their frequent complaints about the regrettably inviolate contract they had signed agreeing to complete the project were a constant source of amusement for off-duty demons), but Satan took no interest in it. He had assigned the majority of the work to some of the duller lieutenants, and, predictably, they had gone about the project with an eye towards size, expense, and a ridiculous, clichéd, overblown sense of evil. They were all fire and no brimstone: they cared nothing for art and everything for function, and even here, in a place where their sway was absolute and unquestioned, they were devoted to grotesque displays of power. Many were the times Satan regretted the necessity of doing away with the more spirited and bright of his fallen angels.

As a result of this state of affairs, he rarely went to the areas beyond the Ninth Circle; it was too jarring to pass from the desperate, awful beauty of Mulcimer’s restrictive, inwardly collapsing miniatures to the hypertrophied, egregious excess of his inheritors. It was too much of a reminder of how the light-bringer really had fallen, and he would become melancholy when he considered that his future might be that of the supervisor of an efficient, bombastic, pointlessly huge torture factory. But today, in aid of making sure that future did not become his past, and to fulfill the ancient obligations that kept him underground, to the Tenth Circle he went. Since construction was not yet complete on this level, the shades who would someday permanently reside here were being housed in shabby temporary buildings. This was the idea of some of the mortals subcontracted to build it, and the younger demons who supervised construction thought it was an absolutely smashing idea. (The mortals, when they heard this praise, asked if they might be vouchsafed a day off. This provided senior management with such a good laugh that they decided to actually let them have one, followed by having Amaimon vomit flame on them fifteen hours a day for the next sixty-six days.)

Lucifer looked out upon the latest addition to his morbid kingdom, and was not pleased; he was never pleased. He was given a vast realm to make his own, but there were limits to even his power: he could not make a Heaven of Hell. Each day of the last million that he set foot outside his throne room he was made to understand what punishment really meant. His eyes told him what his heart would not, that he was the lord of a territory of burnt earth and dried clay from which nothing truly divine could be fashioned. Mulcimer’s designs had possessed a horrible beauty; his was the soul of an artist, who took what he was given and made it into something awful and mad and full of wonder. But Satan’s was the soul of a scholar, an administrator, an inventor, a ruler. He was not happy taking what he was given, and he had never wanted to make a small something of a big nothing. Thinking of the old man made the Prince of Hell wonder what the architect might have done with Heaven. With a home truly worthy of his incredible talents, what might he have done? What wonders could he have wrought in the Temple of God? What could he have done with the massive, impossibly majestic walls? How might he have fashioned paradise? What intricate gardens might he have tended on that perfect, eternally peaceful Western Slope?

The Devil was shadowed by something very close to guilt; he was an eternal advocate, for obvious reasons, of the notion of individual free will and moral agency, but regardless of the fact that Mulcimer had made his choice to throw in his lot with Satan’s forces, the Prince of Hell still felt some regret that he was the cause of the architect’s age-long waste, of the pissing away of golden talents in a leaden cave. Of late these emotions so common to the merely alive, as opposed to the eternally living, had pestered him like a night-bug. For the last several years, he had found himself far too often preyed upon by bothersome sensations like guilt, regret, frustration, impatience and doubt. These latter two in particular worried him; an immortal who finds himself seized by impatience is one who must quickly master it or go quite insane, and the ruler who oversees an intricate hierarchy of the malignant, deadly and ambitious cannot afford many moments of doubt.

Why he was recently harried by these feelings, he could not say; his rule was secure, his short-term plans had not been interfered with, his larger projects were progressing smoothly, there had been no serious challenges to his authority, and his relationship with Plutus was mutually profitable and beneficial. The death of the old man had troubled him, it was true, and left him with precious few in Hell he would call peer; and the ever-increasing thinning of the number of his fellow immortals, while not disturbing in an emotional or sentimental sense, struck him as an overall loss from a tactical standpoint. But neither of these things adequately explained a mood which the poets in his dominion, were they allowed a moment’s pause from being drenched in honey and set upon by angry bears, would have described as “melancholy”.

One thing that disturbed him was the intelligence he was receiving from Heaven. Although he had not seen with his true eyes in many thousands of years the City of God, that vast pinnacle of divinity he had once called home, powerful magics were at his constant disposal, and he still had some truck with the celestials who, through surrender, victory, or diplomacy, had been spared Jehovah’s wrath and been allowed to remain in Heaven as servants or advisors. A few were his entirely, moles in the ministry of God; a few others were at least willing to be suborned, either by the currency of Plutus or by the promise of favor in the event that Satan ever fulfilled his persistent fantasy of marching, bloody, smoke-blackened and victorious, through those magnificent gates. And of late, these sources and his seers had told him that the Lord was in a state of rather pronounced agitation, even for Him. And when the King of Kings was agitated or upset, it usually meant that the house of Satan would soon be plagued.

On through the vast Tenth Circle walked the power of the air, treading lightly on dust and sweat and powdered stone that spread across it like a fine paste, an omnipresent sign in the cavernous enormity of the still-nascent addition of the work constantly being done. Past the sad, shabby little temporary buildings made of weak tin and processed misery did he walk, well pleased at the sense of impermanence, pointless flux and despairing ambition they created. Growth for the sake of growth was one of his best ideas, and it had seized the mind of man with a tenaciousness that surprised even its author. One of the things he loved the best about humankind was its ability to completely embrace ideas, any ideas, no matter how inherently foolish they were, without a moment of doubt or reflection. His frustration and ambition aside, and considering his intolerable defeat and banishment, Lucifer was always pleased at a job well done.

Finally he arrived at the Keep of the Tenth Circle, an overblown monstrosity of white marble and gold that hadn’t been good enough for Plutus. The demons on the newer levels saved the finest work for themselves – or so they thought; Lucifer himself would have preferred the depressing honesty of the trailers to this would-be grandiosity. With the sort of show of obeisance and faux-regal pomp that he had so detested in Heaven, a platoon of imps (none of whom he recognized; there had been a time, and it didn’t seem that long ago, when Lucifer had known every celestial in Hell by name) escorted him to the acting commander, Tartarachus.

The demon, a sallow bat-skinned thing with withered wings and a pinched merchant’s face, sat stooped over a table in the plaster-dusted great hall of the keep, forsaking the pomposity of its throne (which sat under a massive drop-cloth which could do little to disguise its hyperactive grandeur) for a tall high-backed wooden chair at a long table. When the Prince of Hell was announced, Tartarachus was poised above a ledger; he seemed somewhat reluctant to abandon his accounting; but he knew his duty and stood to his full height – some nine feet, dwarfing the merely tall Satan, who nonetheless held the command – and bowed deeply. “Hail Satan,” stammered the lanky demon, in a wavering voice filled with the expectation of an angry answer, “Prince of the Realms Below and Bringer of Light.” He said the words in a way that expected punishment for having forgotten some detail.

“Hail Tartarachus, Keeper of Hell, appointed over punishments,” recited Lucifer in a rote manner, tempering his impatience. “What are you doing down here? I thought this would be something Procel or Caacrinolaas would be taking care of.”

The Keeper of Hell shrugged. “Procel is on top of it, but he’s upstairs influencing some scientists, or something. I told him I would take over since there’s a lot of stuff to take care of here in order to keep on schedule. And frankly, I need this to keep on schedule. The last batch was huge, and I’m short-handed as it is.”

Satan folded flat his twelve radiant wings and sat across from Tartarachus, his crooked eyebrows hitched with curiosity and more than a bit of annoyance. Tartarachus was the master of the damned, and supervised all the punishments of the shades; his last shipment of the tormented dead must have been unusually large. Which meant that the Prince of Hell would probably have to spend several days down here, doing token meet-and-defeats of all the new arrivals. “Why short-handed? Don’t tell me they’ve got you doing paperwork.”

“I’m telling you. Technically, this whole section falls under the jurisdiction of Gaap, so he gets to allocate all the resources. As you can see,” he groused, waving a dismissive horned hand at the impish color guard, “he’s got all my people assigned to this idiotic suck-up detail, so I’m having to fill out all the requisitions myself. It’s unbelievable.”

Satan smiled a winning smile. “Bureaucracy works, Tartarachus. Remember, once the construction is finished down here and we get the zoning taken care of, all the shades will go back under your department, and you can make Gaap’s life miserable for the duration.”

“I know, my lord. Forgive my impertinent complaints. It’s only that I’m ridiculously overbooked at the moment. Do you know that they’ve even got me personally tormenting some of the damned?”

“You can use the practice, Keeper,” Satan laughed. “You’ve become a rubber-stamper. I think the last case you personally handled was one of the bad popes. Anyway, why you? What happened to Puruel? Don’t tell me he’s on Earth; he never leaves home.”

“Well, no, he’s not upstairs. At least, not anymore,” the demon muttered, casting around the empty hall with his yellow, torn eyes to avoid looking directly at his master.

“Puruel was on Earth?” demanded Lucifer. “For what reason? Who authorized such a thing?” Tartarachus sat stooped and silent for many long seconds. “You had best tell me, Keeper. Your position is not a sinecure. I am sure that many of your underlings have not forgotten what you did to them when they were shades.”

“He…it was authorized by God, my lord,” stammered Tartarachus. There was fear in his voice now, an entirely different specimen than the mere anticipation of a dressing down. When Satan chewed you out, it was usually in an agonizingly literal way. “He demanded of us the loan of Puruel for the commission of certain rites. We…I knew nothing about it until only a few days ago, when he returned with a shade. Who wasn’t on any of my invoices, but he had permission directly from Heaven. Everything was in order, and…”

“Tartarachus,” hissed the Devil, his normal warm, rich tones reduced by anger to a sinister serpentine whisper. “I have tried to make this clear to all of you. Jehovah commanded me when I was the regent of God. He does not command me now. I am the lord of Hell, not He. We honor the covenants and treaties we have made with Heaven, but it has no right to issue fiats to us and to take from us our servants. By what authority did he ‘demand’ the loan of Puruel?”

“I, I do not know, my lord. I was not privy to those negotiations, which were made by Prime Minster Beelzebub. I only know that Puruel’s services were tendered to agents of Heaven and he has only just returned.” Tartarachus seemed to have been emboldened by his fear, and words spilled out of him at a rate that only panic can inspire. “He is there, now, with the shade, in fact. That’s why he’s not supervising the torments, even though he is back from Earth, you see, because part of the agreement is that he personally supervise the torture of this shade, because, because, because he is a special charge of Jehovah and…”

“Calm down, Keeper,” Lucifer ordered. “He is with the shade, now?”

“Yes, lord. He is, the shade, he is under strict conditions of punishment and isolation from the, from Jehovah. He is not to be exposed to other demons, or to associate with other shades, and his imprisonment is to be absolute. He’s, I don’t even know if should be telling…”

“What?” A silence like cold death chased away the oppressive heat of the chamber. “You don’t know if you should be telling me this? Well, I expect not. After all, who am I? I am only Satan, the light-bringer, the Prince of Hell and your lord. Why should you owe me any loyalty? Obviously you jump at the voice of He who exiled me here, but you spare no consideration of me. Perhaps you would be happier working for Him, eh? Perhaps He would receive you with open arms. He is notoriously forgiving, after all. But I am not, Tartarachus. I am not prone to forgiveness in the least.”

“No, lord. I mean, yes, lord. I apologize most abjectly, lord. I spoke out of turn, lord. My place. I did not know my place, lord. I.” A thick barbed tongue lolled around in the Keeper of Hell’s huge mouth, trying to pin down the right words to placate the Prince of Darkness.

“Don’t abase yourself, creature. You are overworked and have forgotten your manners, that is all. Only keep in mind, I ask you, whose kingdom this is, and who commands it. Where is this very special soul being kept, if I may inquire? Am I allowed to speak with him?”

“He is in one of the caverns, here on Ten, lord,” answered the Keeper, his taloned fingers fumbling through the papers on the great table. “I have the requisition here, in fact, and actually, er, as it happens, the, Jehovah has requested that in fact…”

“No, I can’t talk to him. That is what you are dancing around, yes?” The demon nodded, his mouth agape but silent. “I am in no mood to be bullied by that plague rat today, Tartarachus. I will speak to whoever I choose. Take me to where this shade is kept, and we will see what he has to say. After all, he’s not Jesus.”

The tiny cave in which lay the shade of Adam Kapernekas was featureless, dull and cramped, and inspired neither pleasure nor terror; it was hardly the sort of environment in which the damned were normally kept, particularly if they had done something so awful as to deserve the personal attention of God. However, it was one of the only permanent structures in the Tenth Circle of Hell, and one of the very few which was far away from the everyday traffic of shades and demons. So here he was kept, to honor the demands made by the Lord of Hosts, and here he remained, in the company of the only living being he had seen since the day he died.

Since his mortal death at the hands of the archangel Michael, which seemed to him untold years past but in fact had been less than a week ago, he had found himself transformed into some immaterial , half-formed duplicate of the man he had been. He lay completely unmoving on the floor of the small, dusty cave, his eyes affixed on the featureless ceiling if for no other reason than to avoid looking at the horrid demon Puruel, who was his now-constant companion. Adam did not sleep or eat; his time in the cave was stultifyingly uneventful, an unending sentence of empty time only occasionally punctuated by the ashy silent demon thrusting its crude dagger into what should have been his body.

It caused him excruciating pain when this happened (there seemed to be no regular interval to the process, and certainly he was doing nothing to provoke the torture), pain of a sort both hot and devoid of anything but a metallic chill, pain which he had never experienced or even heard described in his life before. But all in all, it was not terrible; it was infrequent, quick and even tolerable. If this was Hell – and Adam had no reason to believe that it wasn’t – he at least held out some hope that he would go insane before the pain and boredom became any greater.

It had been, he thought (wrongly), several days since Puruel – who now sat at the mouth of the cave, rocking back and forth on his haunches in the odd animal-like way he had, his veins no longer afire but merely coursing, like lava floes, just below his skin – had stabbed his insubstantial body with that soul-searing blade. It seemed, in fact, like such a long time that he began to wonder if Puruel had simply forgotten him, or was ignoring him altogether in hopes that the tedium would destroy him more utterly than any physical or psychic pain. After all, even if he’d wanted to, there was very little Adam could do: he could roll his phantom corpus from side to side, he could move his “eyes” and much of his “head”, and he could sit up very slightly. But he could not feel the cold stone of the cavern against his naked flesh; he could see through his own ghostly form; and some time ago, he had noticed the ability to move his fingertips, but when he did so, they did not even slightly disturb the dust on the floor of the cavern.

Perhaps, he thought with what little fear remained in his nearly-exhausted supply, nothing will ever change. Perhaps this will be my eternity: infinite epochs staring at a dark stone overhang, and nothing more. I wish I could go mad, he thought, and then spared himself a contemplative moment: perhaps the eastern religions are right. Perhaps if I negate what remains of myself, I will achieve oblivion. Perhaps I can cease to exist. It would be a blessing, he knew, considering what had gone before. It was a rather distant hope – it seemed very unlikely, having seen all that he had seen, that Buddhism or Hinduism might be correct after all – but it was the only hope he had left.

It was, however, a hope that vanished in no time, as the demon Puruel began to leap agitatedly about, and soon burst into rivers of bloody flame and lowered himself into a backwards-scooting pose of abjection as the regal commanding figure of Satan, Lord of Hell, ducked into the cave. Although he thought himself long past the capacity for surprise, Adam Kapernekas nonetheless found himself wondering at how precisely the Devil looked like many cultural representations of him. He was tall and dark and unavoidably handsome; a hooked goatee sprang out from a strong chin; and his movements were delicate, considered, and precise. He even wore a suit, a modern men’s dress suit of exquisite cut. Aside from his age (he appeared to be in his late 30s, although the absurdity of that notion would have made Adam laugh if he weren’t a slaughtered shade being tortured in Hell), he looked extremely similar to the young attorney who had handled Adam’s probate issues when his parents died. Some elements were missing: there were no cloven hooves, no horns; there was none of the red skin/pitchfork/ pointed tail fantasia of popular iconography; and he appeared to be smiling – an awful, indulgent, terrifyingly friendly smile – but there were no fangs to be seen. The manila file folder he carried in his right hand seemed to be an incredibly incongruous element in the setting, but Adam’s mind gibbered so from the impossible images it had been exposed to in recent times that another one seemed hardly to make a difference at this point.

The Lord of Lies consulted a folded piece of paper in that very vessel – a piece of parchment, from the looks of it – and spoke, at last, to Adam. His voice was pleasing, that of an actor or a doctor or a caring family friend. Adam was shocked to hear such a pleasant voice after the horrors of Michael and Baal, but hidden in that warmth was a terror. Adam knew who Satan was, and he knew that the greatest mistake he could make would be to trust him or believe him. “You are…”, a pause as he consulted the parchment, “Adam Kapernekas?”

Adam tried to speak, to say yes, but he found there was no sound. The Devil, though, seemed to hear him just the same.

“Good,” he said. “That’s one obvious possibility out of the way: they haven’t sent me the wrong person. Do you know who I am?”

Adam dared not respond, voice or no voice. To this question he simply nodded his head. His body, back on earth, had no head; it was sort of nice to have one here, even if solid objects tended to pass through it.

“Good,” repeated the Tempter. “Then there’s no need for any introductions. You know who I am, I know who you are. Still, you have the advantage of me: you know what I am, as well. And I haven’t got any idea what you are. Perhaps you can help me rectify that oversight, Mr. Kapernekas.”

Scholar, Adam said but did not say. Again the Devil seemed to hear.

“Well, that’s interesting, but not especially helpful,” the Devil replied. “Jehovah is not particularly fond of scientists, but he rarely sends them down here. Too much trouble. Can you provide any insight as to why you’re here, Mr. Kapernekas?”

I, he thought, and wondered if this would be his speech through an eternity of pain. I found a staff, a piece of wood. He stopped himself; even after all he had seen he did not wish to aid the Tempter. I don’t know why I’m here.

Satan shook his head slowly, as if in reproach or disbelief. “Mr. Kapernekas. Honestly. I am the Father of Lies. Do you think your tiny efforts at untruth can thwart me? You are not a fool, or at least not that kind of a fool. You know where you are; you know who I am. I can assure you that whatever Puruel has done to you,” and here Adam’s phantom form seemed to flicker in an out like a staticky radio signal, as if his soul were still cowering at the sense-memories of his body, “I can arrange for something a thousand times worse without even thinking hard. Now if you please, no further lies. I sense belief and faith in you, but I also know who sent you here, and you may be assured that I can treat you better than He did.”

Adam’s shade did not move; his face – a blank of far-away pain – didn’t either. But his mind whirled. He was still of the newly dead, and had seen his cosmology, once a distant and generalized thing, come to stunning, hectic life and then explode in his face like a dynamite bomb. He no longer had any idea what to think, how to behave, what moral compass to follow, what spiritual values to cling to: all he wanted was to avoid pain. He saw a vivid eternity of agony looming before his view like Everest, and he decided then that he would do anything, say anything, ally himself with any evil in order to reduce it even a pebble’s worth – and pray that in so doing he was free from the vengeance of God. Inside his head, privy only to Satan, he spoke again: I was sent here by an angel.

The Prince of Hell narrowed his perfect golden eyes. “An angel? Are you sure you aren’t mistaken? There are many entities in Heaven and Hell who…”

It was an angel, I know it. I even know his name: it was the archangel, Michael, the good right hand of God, the commander of the armies of Heaven. Adam let his mind flow open as he wished he could his living mouth; separated for the first time in his long death from the savage, unspeakably cruel Puruel, he felt a tremendous sense of relief and release. It made him feel, not happy or good, but somehow less afraid, to talk.

“Michael.” Satan pondered this. If it were true – if the shade had been sent here by that arrogant, vicious time-server, if the Lord had truly requisitioned Puruel to assist someone as mighty as the angel of war – that would explain the extreme veil of secrecy around the miserable man. “And what would the good right hand of God want with your little life, shade? Who are you that the most feared of the Heavenly Host demands your life and your soul?”

Before Adam could answer, the demon Puruel began shaking and hopping in an agitated fashion at the mouth of the cave. His empty face made no sound but his flame-riveted feet padded manically about on the stone floors and his nails scuttled noisily against the walls. The Lord of Hell turned sharply and glared at the fiery, pitiless demon; he spat out a string of words in a language that Adam vaguely recognized as similar to, but somehow debased from, the strange celestial language that the archangel Michael had spoken in those terrible hours in the Chicago apartment where he left his mortal shell. Bobbing and ducking in his silent, frantic, menacing way, still Puruel said nothing, but communication was nonetheless clearly taking shape. The Tempter’s words became heated, and indeed the temperature in the small dark empty hole seemed to increase; then, without warning, Satan waved his hand and folded it into a loose, curling fist, and the demon Puruel simply vanished. One moment he was in the mouth of the cave, popping and hissing and fretting and blocking out the meager light of Hell, and then there was a crackling lick of flame, a slight airy sound and a faint brimstone odor, and where he had been was dark nothingness.

When Satan turned to him again, he seemed angry, menacing for the first time, as if something he had picked up from the demon had infuriated him. There was a tone of impatience in his voice when he spoke. “Mr. Kapernekas,” he said, “This is Hell. You are damned. All that you learned in your short and wasted life about what happens here is truer than you could have possibly imagined. You have received the mildest of treatment at the hands of Puruel, for reasons I cannot at the moment determine. However, nothing in the covenant that binds you to this place prevents me from subjecting you to far greater agonies. You are not to be allowed to mingle with other souls, and you are not to be interfered with by others under my employ. But Puruel is still my subject, and if I were to so instruct him, he would make each of your subsequent days, and those days will be never-ending, more miserable than the one before. Since I am already violating a contract by speaking with you, and since I rashly removed Puruel in a moment of pique, I am in no mood for evasion. Please tell me at once why the angel Michael sent you here. If you are truthful and concise I may ease your pain. If not I shall still learn what I want to know, and you will suffer immeasurably in the process.”

I am…I was on an archaeological dig in Syria. The site collapsed, I think it was an earthquake. There was a ruin below, and a monster lived there. He said he was Baal. Adam found himself actually anxious to tell the story.

“Baal?” the Devil queried. “I thought he’d died thousands of years ago.”

Not alive, corrected Adam. Michael killed him. But this is later. In the ruin, the monster – Baal – he ate a child. He thought I brought it to him but I didn’t, I swear I didn’t, I don’t deserve to be here, I’m not…

“You are becoming hysterical. Calm yourself.”

The words had a profound effect on Adam. Before he died, continued the tortured soul, he gave me a staff. He said there was a goddess inside it, that God would want to destroy. He told me to take it far away, and to hide it in a place that was beyond the reach of the Lord, and I did, but I don’t know why I did. It was as if I was possessed, so quickly did I do it. And when I came home, Michael and the demon took me, and they asked me where I had taken the staff. They did terrible things to me. They said if I told them where it was they wouldn’t hurt me anymore but they lied. I told them and they did it anyway.

“Yes. Jehovah is notoriously poor at keeping His bargains, considering the importance He assigns to contracts and laws. It’s a trait I’ve always found bothersome in Him.” Satan transfixed the shade of Adam Kapernekas with his beautiful, impossible eyes. “Adam, this is very important. Do you remember the name of the object you were given by Baal?”

Yes.

“Was it the Wood of Asherah?”

Yes. “And you told Michael where it was.”

Yes.

Satan pondered this with great intensity. Behind his golden eyes was a tornado galaxy, a beehive, a torrent of possibilities. “Well. That is an interesting development, isn’t it? I can see why He didn’t want me to speak to you. I can also see that I will have to act quickly. So I need you to tell me what you told Adam. I need you to tell me where you placed the Wood of Asherah. Will you do that, Adam?”

Yes, said Adam for the fourth time, and told him.

“Cold climate. Nicely done. Well, thank you very much, Adam. I’m sure you’ll forgive me but I must attend to some business rather sharpish.” And with that the Prince of Hell turned and began to duck out of the cave and back into the halls of dead.

Wait, screamed the remnants of Adam’s soul. What…can’t you do anything for me? Can’t you help me? I…I helped you.

Lucifer smiled, and the devil’s grin was cruel. “I’m sorry, Adam. There’s really nothing I can do. You are bound for eternity here, and it will be a savage eternity indeed. I wish I could help, but I am bound by the rules of Heaven, as are we all.”

But…but… Adam stared down the barrel of a horrid, bloody forever. You’ve already broken the rules. You spoke to me, and you…you have already gone against the laws of Heaven.

“That was for my benefit, Adam,” came Satan’s answer. “Why should I trouble myself for you?” And with that, the Lord of Lies left him to damnation.