It is not often that the events of a single day so crashingly drives home the lessons of a social moment. America had barely raised its head from the pillow after learning of the death in Louisiana of Alton Sterling, a black man hustling bootlegs outside of a convenience store, when it further learned of the death in Minnesota of Philando Castile, another black man driving home from grocery shopping with his girlfriend. In both cases, the men were legally armed (in keeping with the rights so fiercely defended by our country’s conservatives when exercised by white people); in neither case did they do anything remotely threatening to the policemen who killed them. Neither was suspected of a serious crime; Sterling had apparently been mistaken for someone else, and Castile had been pulled over for a traffic violation so minor it would result in a decimation of the American populace were everyone guilty of it summarily executed. Both men were black; both men were innocent; both men were murdered.

I can scarcely believe that things have so utterly degraded — in the Obama era, in what we have come to call post-racial America only with the bitterest irony — that I can bring myself to say that there is nothing special about these police murders. 2015 saw the largest number of young black men in America’s history fatally shot by law enforcement, and 2016 looks as if it will shatter that record with ease. In fact, with only a few exceptions — the willingness of the Arab shopkeeper in Sterling’s death to stand up to the official police narrative, Castile’s status as a solid citizen, and the fact that both murders were largely captured on film and seen by millions — the twin killings have played out almost according to a script. It’s a predictable one, too, because the cops never get tired of remaking it: police kill an unarmed black American; outrage and counter-outrage is generated; it becomes painfully clear that the victim had been no threat, but the police insist they were afraid for their lives; a media narrative is spun about how the victim was no angel; the judicial process drags along slowly enough for the public to lose interest; and if charges are ever made — and they usually aren’t — they are dropped, or result in a not-guilty decision on the part of the killer cops. If the history that judges us miraculously possesses any kind of moral sensibility, it will wonder how we could possible let ourselves get bored by this.

If there is something remarkable about the murders of Sterling and Castile, it is how completely and rigorously they highlight so many urgent social questions. Of course, first and foremost, there is the issue of racism; there is no chance — none — that either of these men would be dead if they were white and doing the same things, or worse. Castile, by every account (and there are people working non-stop as I write this to paint him as a monster who deserved to die) a law-abiding and decent man, had been pulled over dozens of times for minor traffic violations before some cop with a shaky trigger finger gave him the death penalty for a broken taillight. Sterling was pumped full of bullets for things that white kids joke about doing on Twitter. Racism is certainly not the only issue at play here, but it is the most prominent one; it is the absolute and irreducible factor in all these deaths, the one thing that cannot be reformed away, the rotten tumor on the beating heart of America. Anyone who thinks racism was not an issue in the murder of these two innocent men is not just an unserious person whose opinion on all other matters should be ignored by association; they are an enemy to human society.

There is more. There is class: both men were working-class, as are most of the victims of police violence. This is especially true of black men, but it is true of people of every race and gender. Sterling, like Eric Garner before him, was a hustler, a cockroach capitalist, a man who tried to support his family by taking advantage of the gray market because the more traditional roads to economic stability, already thick with roadblocks for African-Americans, are slowly being closed off altogether. There is politics: Castile lived in a part of the Twin Cities that has been ruthlessly segregated. There is militarization, the emphasis on feeling threatened where no threat exists, and the deterioration of citizenship on the part of the police. There is big money: Sterling lived in a state that imprisons an unfathomably high percentage of its population, often in for-profit prisons that use a brutal law enforcement establishment to feed them raw materials. There is culture: for generations we have been inculcated that cops are spotless heroes doing a thankless and vital job for which they should be valorized, and not the shock troops of capitalism doing the bidding of a handful of rich property owners lucky enough to write the laws. There is corruption: in the film of Castile’s horrifyingly slow demise, it could not be clearer or more obvious that the cop who shot him knew that he fucked up, and fucked up bad. But you can still hear the voice gradually elevating from terrified panic to self-mythologizing, as he and his partners start blaming the victim and lying about what he did and what he was told to do; and soon enough it will morph into arrogant denial, once he realizes that he will be protected no matter what. And, looming over it all, there is a lack of accountability, a poisonous toxin leeching into every aspect of the very idea of a civil society, a knowledge that no one will be seriously punished for these flagrant and devastating failures of judgement and professionalism, a justly cynical near-certainty that everyone who screwed up will walk. And that certainty will destroy every other faith in the reasonable functioning of our civil society that we so badly need to make sure things work.

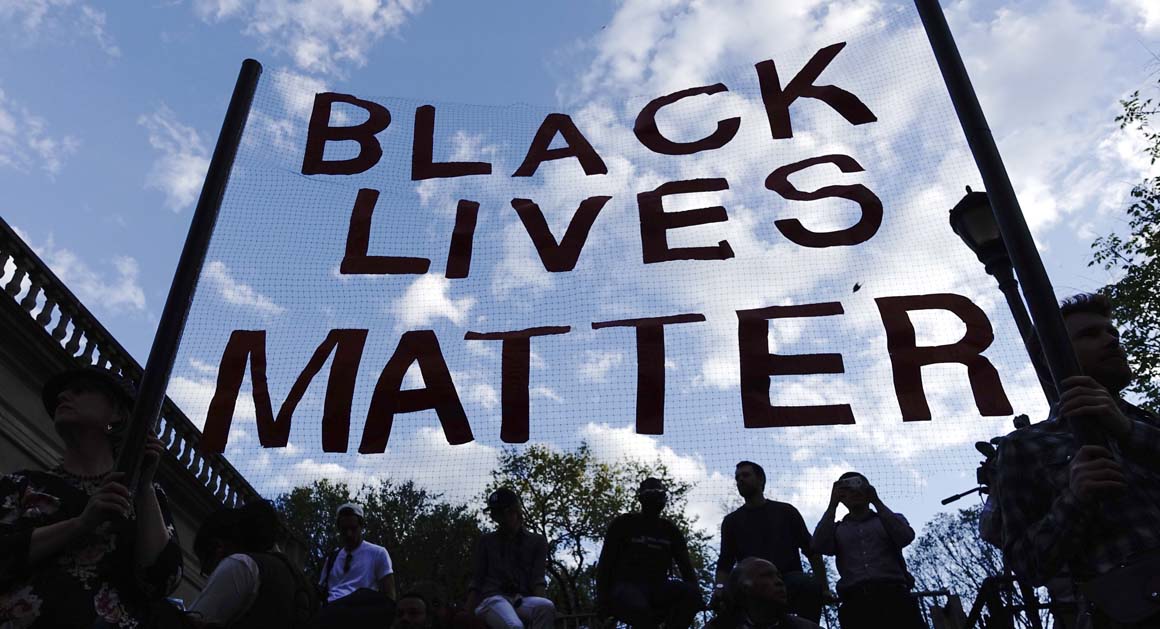

But most of all, what comes across in this double disaster, in this insufferably painful collision of everything that is bad and reckless and wrong about America in 2016, is how important are those three words, BLACK LIVES MATTER. Look, I know: no one needs to hear my opinion about this. I’m not black. My own interactions with the police have been extensive and occasionally ugly; I’ve been falsely accused of crimes, and I’ve been gratuitously assaulted by a shit cop when I was locked up for something I did do. But on my worst day I’ve never faced the kind of risk for doing something that black men face every damn day for doing nothing. I haven’t got any great ideas for fixing this that other, smarter people haven’t already come up with, and the only thing I could add to the discussion is my amazement that black people haven’t risen as one and given the white power structure the merciless ass-kicking it so richly deserves. Nobody cares what I think and I’m only writing this now to try and not go crazy at the sheer maddening injustice of it all. But as much as I may have questioned BLM’s tactics, as much as I might have wondered about their organization and approach and choice of targets, I could never in a million years say I don’t support it, that I don’t understand it, that I don’t want to hear its name ring out from every street corner and statehouse. It is as clear as blood on a white shirt today that, to far too many of the people we have paid to protect our rights and our safety, black lives do not matter. And they must be made to matter, by all means necessary.

Pingback: The Problem With a “Post-Racial Society” – Unity in Diversity