Better Call Saul might have seemed like it was born with the television equivalent of a silver spoon in its mouth. Afforded every advantage by the AMC network, and bringing with it a built-in audience from Breaking Bad, one of the most successful and acclaimed cable dramas of all time, it was almost certain to do well, and its pilot episode was the highest-rated such premiere in television history up until that point.

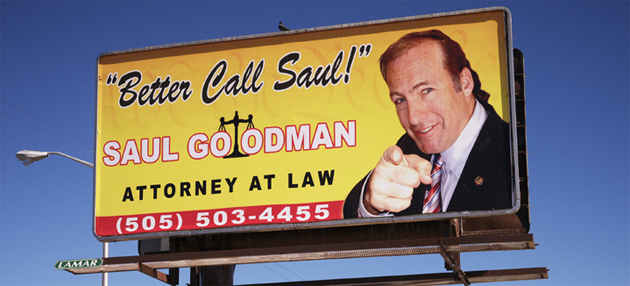

But in fact, Saul faced a pretty steep uphill battle. For all its privileges, it had a lot going against it: not just high expectations, but the inherent difficulties common to all spin-offs of pleasing critics and fans of a popular predecessor while still finding its own voice and trying to become something more than just a carbon-copy. Better Call Saul was an even tougher nut to crack: Bob Odenkirk’s shady attorney Saul Goodman was a popular character, but it was unclear if he was the kind of breakout character that could sustain an entire series. Odenkirk was a terrific comic actor, but it remained to be seen if he had the heft to support a whole show, especially one that required a decent amount of dramatic heavy lifting. He wasn’t much of a leading man: 50, balding, out of shape, and with a character actor’s demeanor. And on top of all that, Better Call Saul had a clock built into it: since it was a prequel, not a sequel, to Breaking Bad, there was only so much they could do with the character without fucking up the canon that was already established by that show.

So it’s something like a minor miracle that Better Call Saul, which wrapped up its second season a few months ago, has not only succeeded on its own terms, but, in my view at least, managed to be a better, more palatable show than the blockbuster that spawned it. Part of that is the learning curve: while both shows sprang form the Vince Gilligan production machine, allowing him to bring in some of his best writers and directors (a move that ensured a consistency of visuals in Saul‘s depiction of Albuquerque as a stark, low-rent Jim Thompson fever dream, as well as a continuity of good-quality scripts right from the start), Saul had the advantage of experience, and seems to have learned what made Breaking Bad work while avoiding the missteps that sometimes hindered it in its latter seasons.

At its heart, Better Call Saul is more of a character study than it is a crime drama, so the proper casing was critical. New additions like Rhea Seehorn, the oily Patrick Fabian, and the never less than excellent Michael McKean as Odenkirk’s disapproving older brother have worked out well; Seehorn lends the plots a bi of tragic, exasperated futility, as she embodies an overlooked, career-savvy women who never takes the kind of shorts that she can’t resist finding attractive in the man who is still Jimmy McGill. McKean’s electromagnetic hypersensitivity is a total wild card of a character trait, and it’s one that I expected to find annoying and frustrating; it turns out I was right, but the script makes room for that interpretation while still letting Odenkirk treat it with deadly seriousness out of fraternal concern. I’ve always found Raymond Cruz gratingly over-the-top as Tuco, but he’s balanced nicely by the preternatural malice of Mark Margolis as Tío and the welcome addition of Michael Mando as the calculating Nacho. Kerry Condon adds grievous moral weight as Mike Ehrmantraut’s daughter-in-law Stacey, and no show has ever suffered from bringing in Ed Begley Jr. or Jim Beaver.

The nature of Better Call Saul, however, means that it must live and die on the strength of Jimmy McGill and Mike Ehrmantraut. The latter’s backstory, teased out in bits and pieces in Breaking Bad, is fully realized here, and it doesn’t completely work for me; its Michael Coreleone-style family ethics carry a lot of dramatic heft, but the big reveal of his role in his son’s death felt a little too melodramatic to me. Jonathan Banks is always fantastic, though, and he plays Mike with zero cool and maximum weary professionalism, harking back to a Hawksian masculine archetype that has been overpolished of late. It’s nice to see its rough edges return.

Bob Odenkirk, of course, has been a revelation. His ability to handle everything required from him in the role of Jimmy McGill — cowardice, ambition, cockiness, cleverness, humiliation, betrayal, pride, skill, good humor and terrible dark moods — has proven that he’s vastly more than a great comedian. But while his acting demands the recognition it’s getting, we shouldn’t forget what a terrific character Gilligan and company have created for him to play. Saul Goodman was a familiar figure, a scruples-free hustler who’ll do anything provided it pads his bank account and keeps him out of danger; he was allowed some character development, but only insofar as it showed him what a mistake he’d made to plunge himself so deeply into the affairs of Walter White. Jimmy McGill, on the other hand, is much more satisfying, and a refreshing break from the normal Difficult Man model: Jimmy is a hustler, yes, and a guy who lets his laziness get in the way of his talents, and a man who struggles to find his limits.

But he is also a perfect model of the Great American Fuck-Up: he is a man who clearly tries to do good, or at least not to do bad, or at least least not to do too bad within the wobbly corners of good and bad he’s defined for himself, but is frustrated at every opportunity. The system, the authorities, the realities of the law, the necessities of capitalism, the murkiness of what is right and what is possible, even the often-delusional desires of his own clients constantly get in his way. And no matter how hard he tries, no matter how competent or even gifted he proves himself, there is always someone — a judge, a banker, a lover, an associate, even his own brother — for whom he will always be a failure. And it’s that perception of himself that drives him to actually be a failure, right when he’s on the verge of success. The power in the character of Jimmy McGill, who I can’t wait to see again next year, is that every person who believes he can never truly be a good man pushes him a little bit closer to being a Goodman.