I’ve been thinking a lot about political violence.

The election of Donald Trump has brought with it a significant escalation of the rhetoric that he is a dangerous fascist, and that things are about to get serious for Muslims, women, and LGBTQ people, to name a few. And, indeed, this is a critical time for the Trump administration; having been handed the keys to the White House — which, it must regrettably be noted, includes access to drone warfare, targeted assassination, and a security/surveillance apparatus he will inherit from Barack Obama — we will soon learn if his blunt endorsements of belligerent nativist nationalism are sincere or just rhetorical bluster. Robert Paxton, perhaps the most brilliant man to study the topic, places this as the most important transitional time in his 1998 essay “The Five Stages of Fascism”: that moment between the acquisition of power and the exercise of power.

But, just as we must ask ourselves what we can expect from a Trump-led government in terms of violence, we must ask ourselves what we are willing to do about it. It cannot be denied that many of the voices that were raised the loudest in warning us that Trump is the second coming of Adolf Hitler are the same voices that are, if not actually preaching conciliation and cooperation, at least warning us that we must not surrender the moral high ground in letting peaceful protests turn violent. The scolding sound of respectability politics has become a dull roar this week, as various proper noises are made about the peaceful transition of power, the continuity of governance, and the importance of holding on to our moral authority. Politicians, pundits, and cable comedians alike are raising a chorus of prudence and moderation, urging us not to damage precious property, to keep our dissent within the realm of decency, to not rob the ‘good’ protestors, who shake the hands of cops and don’t interfere with commuter traffic, of their high standing.

Let us proceed from the assumption that violence, in any form, is bad. Of course it should be the last resort; of course it always ends with innocents being hurt; of course it is a plague on mankind. I have always believed that violence, even in its most acceptable practice, is a dangerous monster that is forever at risk of coming uncaged; and that war in particular — the organized mass slaughter of human beings by other human beings — is the single most disgraceful thing in which we can collectively participate. I am not, however, a pacifist. I think nonviolence is admirable — almost impossibly so — but I think that most of its accomplishments must be paired with the often-violent agitation that was taking place at the same time, and that it certainly relies on publicizing state violence, and therefore on state violence itself, to achieve its goals. I believe that there is no violence that can be inflicted on a ruling class that could ever possibly match, either in intensity or in moral weight, the violence inflicted by the ruling class on its subjects. I believe that violence, ugly as it may be, has its uses. But what are those uses, and when — and by who — may they be pursued?

Take the case, for example, of Trump’s vague but alarming threat to require the registration of people of Muslim faith for a database. In theory, this is a horrific position to take, and is certainly in the realm of what we might call a fascist state. But it would also be, under the rules of America as currently constituted, grotesquely illegal. It would violate, at the bare minimum, the First and Tenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, neither of which are likely to be repealed even by a Supreme Court stocked with revanchist conservatives. So even if Trump were to pass a law requiring such a registration, it would be unconstitutional and thus unenforceable. No Muslim with even the slightest sense of self-preservation would show up to register. So the only way it could proceed is if Trump convinced law enforcement and/or the military to go out into the streets and force Muslims under the penalty of violence to comply.

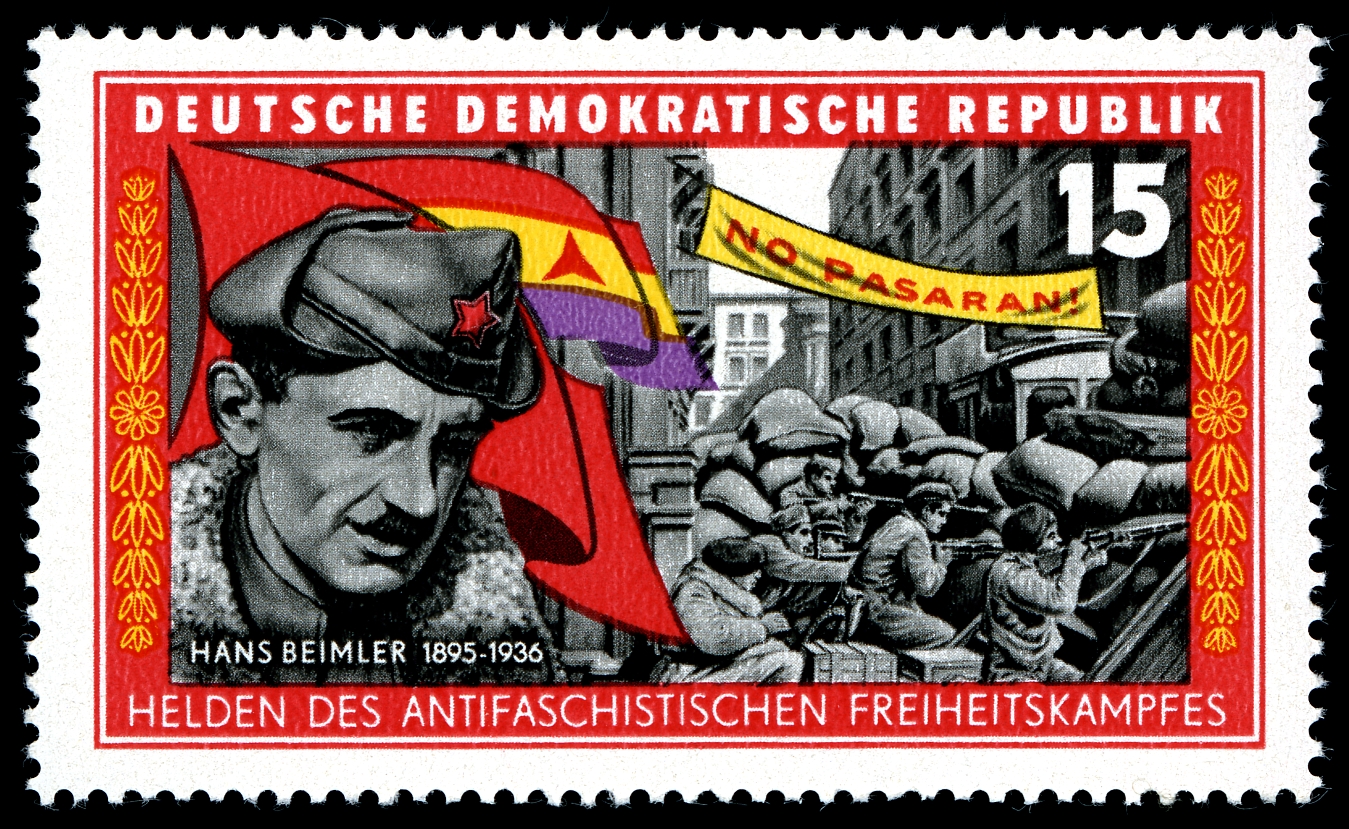

If this were to happen, we would immediately and without question know what kind of leader Donald Trump was, and I very much hope we would know what to do about it. That kind of governance cannot be resisted with petitions, with flowery speeches, with appeals to our better nature, or with the ballot: it can only be resisted with blood and fire. Whether or not Americans are prepared to offer that kind of resistance, I cannot say; it is both entirely theoretical and beyond the scope of the point I’m trying to make here. What I want to establish is that if the worse predictions for a Trump presidency are true — if he is, indeed, willing to abrogate all the laws and standards of our society and pursue the kind of fascist agenda that characterized the inhuman regimes of mid-century Europe — then we must consider that this may only be met in kind, the way the German communists met it when Hitler first rose to power.

But I am not convinced that we have the right temperament. Which is not to say that we should; but it is truly disheartening to be told one day that the American Experiment In Democracy is over and that we should be prepared to enter a New Dark Age, and to be told the next that anyone who throws a brick through a window at one of Trump’s ugly-ass hotels is an Enemy of Freedom. Liberals of this stripe have been stockpiling the moral high ground for so long, they are its only travelers; they have advocated so long for going high when the other guy goes low that they have failed to notice their attacks are sailing right over the heads of the enemy. If they are serious about the alarmist rhetoric they have spread about our Trumpian future, the time has passed to focus disapproving frowns at anyone who takes that rhetoric seriously and does something about it. The last thing America needs right now is well-fed TV squawkers lecturing people who will genuinely suffer under a Trump regime that they’re protesting the wrong way.

If the democratic process is still intact, then we must work ceaselessly within it to change the system, bring the causes of justice and equality to its fore, and block Donald Trump’s moves at every juncture. If it is not, then we had best be prepared to fight. No oppressed people have ever been delivered from their misery by appealing to the better nature of their tormenters, and it is absurd and ahistorical to think you can talk a tyrant out of tyranny with sweet reason and elegant arguments. To return to Paxton, we make the mistake of thinking of fascism, like other -isms, as a coherent ideology when it is not: “Fascism does not rest on formal philosophical positions with claims to universal validity…fascists despise thought and reason, abandon intellectual positions casually, and cast aside many intellectual fellow-travelers. They claim legitimacy by no universal standard except a Darwinian triumph of the strongest community.”

Donald Trump may simply be a particularly execrable president who will do only so much as we let him get away with. If this is the case, we must let him get away with nothing. Donald Trump may also be a fascist in a fine suit, who will do as much as the power he possesses allows him to do. If this is the case, we must teach him how dear a cost the exercise of that power will bear. Either way, the time for bourgeoise propriety and do-nothing finger-wagging is over. Either way, he will not be talked out of the presidency. The old game has been lost; it’s time to either start a new team or write some new rules.