Paul Kingsnorth, it’s safe to say, is a man of special talent. His work with the Dark Mountain Project — one of the only cultural movements to take seriously the concept of a post-human world — and his insightful environmental journalism alone would be enough to establish his brilliance and insight, but he also wrote The Wake in 2014, one of the most astonishing and original novels of the twenty-first century. He followed it up two years later with Beast, the second in a proposed trilogy that is very different in style, tone, and format, but which nonetheless tells an unforgettable story with powerful thematic links to its predecessor.

The Wake concerned itself with a slippery character known as Buccmaster, a small landsman in the north of England, who becomes unhinged and uprooted following the loss of his family to the Norman Invasion of 1066. In Beast, he is echoed and reflected almost a thousand years later in the person of Edward Buckmaster. He once lived in the city, and had a job and friends and a wife and a young daughter. Now he is alone, helpless, hopeless, and far away, living in an abandoned cottage somewhere not far from those same fens that spawned Buccmaster. He doesn’t quite remember, or perhaps just doesn’t care to discuss, how he came to be there, why he left everything behind, or what he is hoping to find; but it’s something. He is waiting for something, on a quest for something he cannot quite name even to himself. Perhaps he is seeking enlightenment, leaving family and status behind, like the Buddha; perhaps he is trying to eradicate himself entirely; and perhaps he is trying to revert to a state of nature, to become like an animal or a blade of grass or a drop of rain. Whatever it is that he’s come here for, he is not finding it, and he is losing his mind.

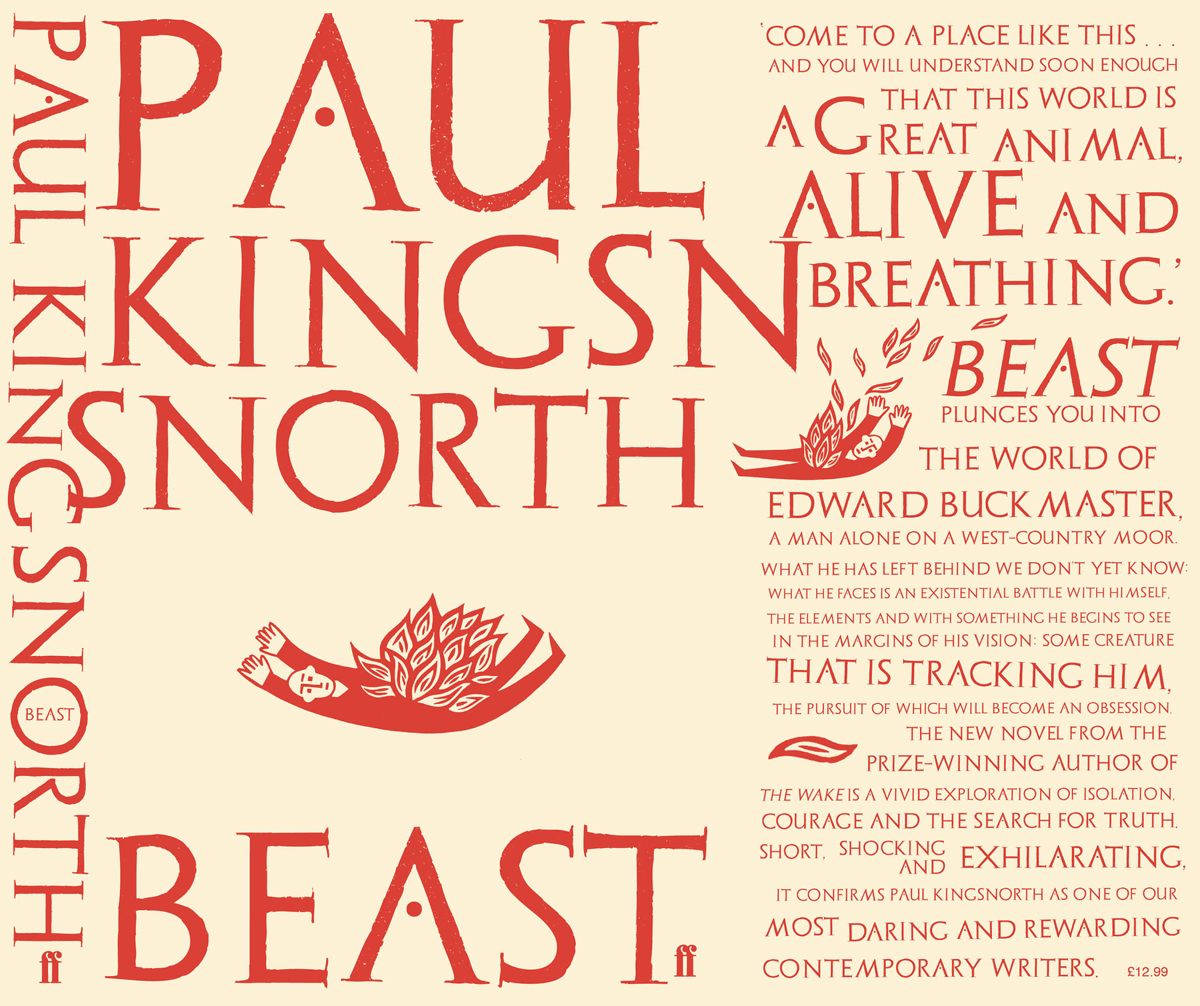

Beast is a very different book that its predecessor. The Wake was a complex, ambitious, difficult book, filled with detail and deep observation, and written in an invented language that conjured a long-vanished time while creating a rhythm and meaning all its own. Beast is much shorter, more direct, simpler, and less specific; it is less like a novel and more like the collision of a dark fairy tale and an extended interior monologue. Its language degenerates and diffuses as the book goes on, but it is mostly modern, direct, and comprehensible. And it is very short, almost more a novella than a full-length work. However, it shares with its prequel a breathtaking prose style, a stunning portrait of a mind in chaos, and an incredible conjuration of place and space that never relents and perfectly illustrates the way a physical location can shape character and vice versa. At no point does its intensity and focus let up, to the point that when we encounter a handful of blank pages that represent disruptions in space and time or momentary lapses of consciousness, it is almost a physical relief.

Despite its brevity, this is not a novel that takes it easy on the reader. It is dazzlingly difficult and particularly relentless, with its pressure and savagery increasing as the book goes on. It is also not the kind of book that brings you a great reward at its conclusion; it is soaked in ambiguity as thick and impenetrable as the fog that rolls in about halfway through the book. Like Buckmaster himself, we often become lost and confused on our way to something we cannot articulate or envision. But the rewards are there; they exist in Kingsnorth’s tremendous prose, and in his unprecedented ability to portray disassociation from civilization and the creep of nature seem simultaneously inevitable, desirable, and horrendously dangerous. Kingsnorth’s vision is similar to that of filmmaker Werner Herzog, but unlike Herzog, his world is not one where humanity loses itself through too much closeness with a nature it fails to fully comprehend. In Kingsnorth’s books, man isn’t really meant to be here at all; he is an alien presence whose submersion into nature is more like the absorbing of a foreign body by a rushing and implacable bloodstream. Not only can we not attain a perfect return to nature, it doesn’t want us to try.

Very little really happens over the course of Beast. Buckmaster is injured when his roof collapses, and never really heals; he sees and senses the presence of a huge black beast that he comes to believe is following him, and sets out to find him, but never really does. (Or does he? It’s a bit of a muddle, as is almost everything that happens to the man.) He comes up with elaborate plans to track the beast and map his surroundings, but never follows through on them; he makes vows and stands on the brink of revelations, but the trigger is never pulled, the epiphany never comes. While we eventually come to learn, through the actions and statements of outsiders, exactly who Buccmaster is and the depths of his delusions at the end of The Wake, Beast allows us no such luxury, and we remain unsure whether we are watching the slow transmogrification of a man into a saint, or the final descent into madness of someone who was never quite sane to begin with. That it manages to create such an exquisite sense of movement and wildness throughout, despite its ultimate abandonment of resolution, is only a small part of what makes Kingsnorth such an amazing writer.

At a time when literature and film is oversaturated with epics, sagas, and reboots, and when sequels and franchises are assumed for even the most modest properties, Beast accomplishes something incredible: it is a sequel that owes everything and nothing to its predecessor, that remains faithful to its tone and feel despite being hugely divergent in content, and that makes readers anticipate the final chapter with an eagerness born of quality and not of obligation. Kingsnorth has created something truly special, and I can’t wait to see what he does with the next part.